Before in this series, we discussed Eulerian graphs and their origins in the seven bridges of Königsberg similarly, there is a a class of graphs called "Hamiltonian" graphs that find their origins in puzzles such as the Knight's tour in chess and the Icosian game developed by the in 1856 by Irish mathematician $\href{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Rowan_Hamilton}{William\text{ }Rowan\text{ }Hamilton}$, the namesake of these graphs.

Same as how a graph is $\textbf{Eulerian}$ if it contains an $\textbf{Eulerian cycle}$, which is a cycle that visits every $\textit{edge}$ exactly once, a graph is $\textbf{Hamiltonian}$ if it contains a $\textbf{Hamiltonian cycle}$, which is one that visits every $\textit{node}$ exactly once.

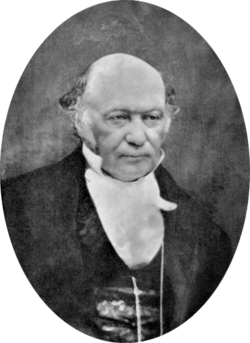

The Icosian game consists of finding a Hamiltoninan cycle on a dodecahedron, which is a polyhedron with twelve flat faces.

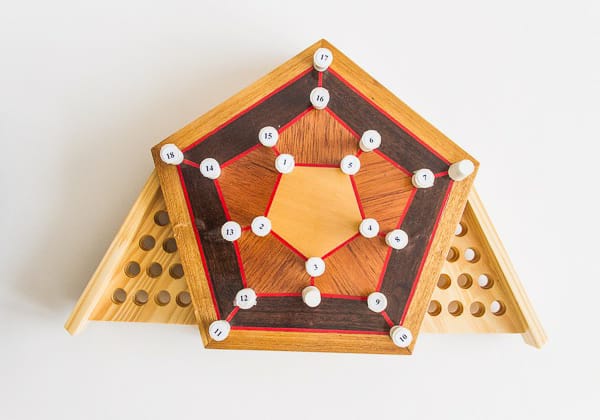

The Knight's tour is the sequence of moves a knight does on a chessboard to visit every square exactly once, if it ends in the first square, then it is a $\textbf{Hamiltoninan cycle}$, however if it doesn't then it's called semi-$\textbf{Hamiltonian cycle}$.

Unfortunately, unlike $\textbf{Eulerian}$ graphs, $\textbf{Hamiltonian}$ graphs do not have a similar characterization, in fact finding such a cycle in a graph is a $\textbf{NP}$-complete computational problem known as the $\href{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamiltonian_path_problem}{Hamiltonian\text{ }path\text{ }problem}$. Both $\href{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriel_Andrew_Dirac}{G.\text{ }A.\text{ }Dirac}$, $\href{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Øystein_Ore}{Øystein\text{ }Ore}$ provided theorems to characterize Hamiltonicity, however in simpler terms, they state that a graph is $\textbf{Hamiltonian}$ if it has enough edges.

If $G=(V,E)$ is a simple graph with more than 3 nodes, and $deg(v) + deg(w) \geq |V|$ for each pair of non-adjacent nodes $v$ and $w$, then $G$ is $\textbf{Hamiltonian}$.

$\textit{Proof:}$

Suppose that $G$ is not Hamiltonian, we consider the graph formed from G by adding edges until any other addition would result in a Hamiltonian cycle. Since we stop before the very last edge that would result in a Hamiltonian cycle, we can find a Hamiltonian path in the graph $(v_1,\dots,v_n)$ , such as the addition of the edge $(v_1,v_n)$ would create the cycle. $\forall i \in [|2,n|]$, let's consider the two edges $(v_1,v_i)$ and $(v_{i − 1},v_n)$ that can exist. At most one of these two edges can be present in our graph, since otherwise the cycle $(v_1\rightarrow v_2\dots\rightarrow v_{i − 1}\rightarrow v_n\rightarrow v_{n − 1}\rightarrow\dots\rightarrow v_i)$ would be a Hamiltonian cycle. Thus, the total number of edges incident to either $v_1$ or $v_n$ is at most equal to the number of choices of $i$, which is $n − 1$. Therefore, $deg(v_1) + deg(v_n) < |V|$, it follows that: $$ \text{If a graph is not $\textit{Hamiltonian}$ } \Rightarrow \exists (v,w) \in V,\text{ such as } deg(v) + deg(w) < |V| $$ Which is the contraposition of our theorem, hence the proof is concluded. $\square$

If $G$ is a simple graph with more than 3 nodes, and $deg(v) \geq \frac{|V|}{2}$ for each node $v$, then $G$ is $\textbf{Hamiltonian}$.

$\textit{Proof:}$

We can immediately deduce the result using Ore's theorem since the condition $deg(v) + deg(w) \geq |V|$ for each pair of non-adjacent nodes $v$ and $w$ is satisfied because $deg(v) \geq \frac{|V|}{2}$ for each node $v$. $\square$

Both these theorems and others that extend to $\textit{directed}$ graphs (eg: $\href{https://zbmath.org/0091.37503}{Ghouila–Houiri\text{ }(1960)}$ , $\href{pdf.sciencedirectassets.com/272566/1-s2.0-S0095895600X01815/1-s2.0-0095895673900579/main.pdf}{Meyniel\text{ }(1973)}$, ..) got generalized by the $\href{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Adrian_Bondy}{Bondy}$–$\href{https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Václav_Chvátal}{Chvátal}$ theorem which uses the concept of $\textit{closure}$ of a graph.

The $\textit{closure}$ of a graph $G$ denoted by $cl(G)$ is the graph obtained by adding an edge to every non adjacent nodes.

A graph is Hamiltonian if and only if its closure is Hamiltonian.

$\textit{Proof:}$

$\Rightarrow)$:

If $G$ is Hamiltonian then it's Hamiltonian cycle exists in $cl(G)$ since it's obtained by adding edges to $G$, then $cl(G)$ is Hamiltonian too.

$\Leftarrow$): Now suppose $cl(G)$ is a Hamiltonian graph,if $G$ is non-Hamiltonian, we can create a sequence of Graphs starting from $cl(G)$ that are Hamiltonians until we reach the first graph in the sequence where the Hamiltonicity is lost (or gained if we go the other way):

$$ G=G_0 \rightarrow \dots G_j \rightarrow G_{j+1} \rightarrow \dots \rightarrow G_N=cl(G) $$

Where $G_j$ is the non-Hamiltonian graph while $G_{j+1}$ is a Hamiltonian one, it follows that the Hamiltonicity is gained from $G_j$ to $G_{j+1}$ through the addition of a single edge that we will denote by $(v_1,v_n)$.

Let's consider now these two sets: $$ X = \{v_i\text{ }|\text{ }(v_{i−1}, v_n) \in E_j \text{ and } 2 < i < n\} \text{ and } Y = \{v_i\text{ }|\text{ }(v_1, v_i) \in E_j \text{ and } 2 < i < n\}. $$

$E_j$ being the edges set of the graph $G_j$, now $X, Y \subset {v-3,\dots, v_{n−1}}$ so $|X|=deg_{G_j}((v_n) − 1)$ as it includes one element for each the neighbours of $v_n$ except for $v_{n−1}$, while $|Y| = deg_{G_j}((v_1) − 1)$ as $Y$ includes all neighbours of $v_1$ other than $v_2$. Then:

$$ |X| + |Y| = (deg_{G_j}((v_n) − 1)+(deg_{G_j}((v_1) − 1))= deg_{G_j}(v_n) + deg_{G_j}(v_1) − 2 \geq n − 2 $$ Therefore: $$ deg_{G_j}(v_n) + deg_{G_j}(v_1) \geq n $$

But then, both $X$ and Y are drawn from the set of nodes ${v_i\text{ } |\text{ }2 < i < n}$ which has only $n − 3$ elements and so, by the pigeonhole principle, there must be some vertex $v_k$ that is a member of both $X$ and $Y$.

The existence of such a $v_k$ implies the presence of a Hamiltonian tour in $G_j$ $(v_1 \rightarrow v_k-1 \rightarrow v_n \rightarrow v_{n-1} \rightarrow v_k \rightarrow v_1)$ which results in $G_j$ being Hamiltonian, a clear contradiction to our supposition, therefore the loss of Hamiltonicity is impossible and the sequences ends in $G$ being also Hamiltonian, this concludes our proof. $\square$

This proof is inspired by the $\href{https://personalpages.manchester.ac.uk/staff/mark.muldoon/Teaching/DiscreteMaths/LectureNotes/HamiltonBondyAndChvatal.pdf}{lecture}$ on Hamiltonian graphs from the University of Manchester.